Seemingly, when Lee crossed over into Pennsylvania he had no short-term tactical plan; he had no point on a map at which he planned to engage the Union Army. His objectives were more political than military. He hoped in any way possible to strengthen the arguments of the Copperheads (the Peace Democrats opposing the Republican Lincoln) and get the Union to negotiate a settlement. If this took a major victory by his army on Union land, he was willing to oblige. He had not liked the position he found himself in at the end of Day 1, but there was little he could do; the game was afoot! The terms set by Buford not by himself.

He held a war council with his Corps Commanders at which time he announced his strategy for Day 2. Falling back on his West Point training, he ordered attacks on both flanks of the Union lines. Ewell’s Corps would do what they had failed to do yesterday and attack Culp’s and Cemetery Hills. Longstreet would attack the south (left) flank of Meade’s Army. But there was work to do. Much of Longstreet‘s Corps was still en route. One of his most trusted generals, Pickett, was the last unit in the marching order having been entrusted with the role of rear guard. Most of the remainder of Longstreet’s men were encamped near Cashtown, safe from detection by the Union observers.

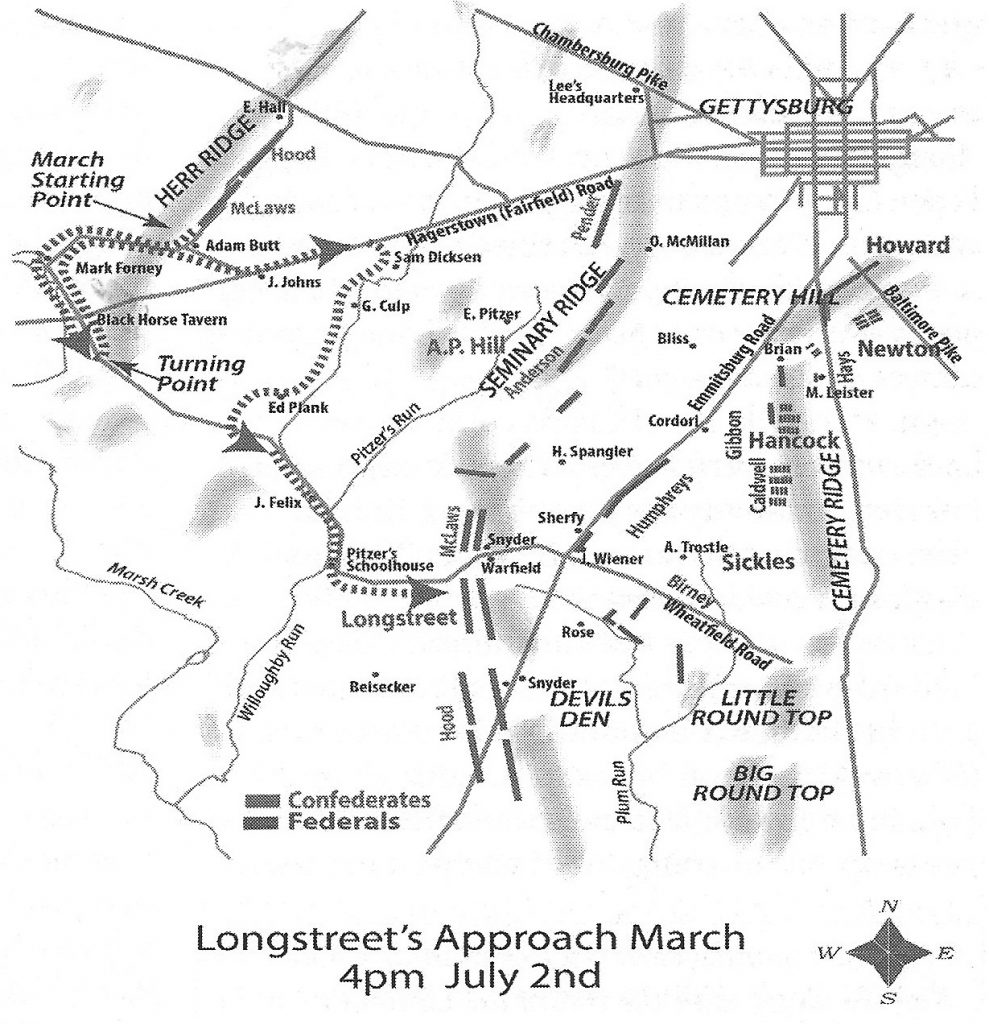

This meant that he had a long march before turning east to launch his attack. Ewell was told to wait until that attack was underway before he engaged. Throughout the night as Day 1 became Day 2, Lee listened to the sound of wagons and orders from the ridge a mile away as the Union units arrived one after the other and were ordered into place along the growing defensive line. By morning, Little Round Top was sparsely manned. It was a militarily vulnerable position, but it wasn’t Lee’s main target. But Longstreet was not yet in position. It was actually late afternoon (around 4PM) when he was finally in position to attack. Pickett had still not arrived.

By that time, Little Round Top was more heavily defended and since the rocky terrain of Big Round Top did not lend itself to a defense in depth, it was occupied by sharp-shooters and perhaps most importantly a Signal unit. That Signal unit using flags could convey information rapidly to Meade’s HQ. They would play a vital role in the outcome. Meade had established his HQ in the crook of the J and with a line that ran barely 3 miles end-to-end, he had a good overview of the battlefield. He also had about 17,000 soldiers per mile aligned to defend.

Early in the day, LTG Sickles saw what he thought was both a vulnerability and an opportunity. Forward of his position on Little Round Top, about half-way to Seminary Ridge, was another hill called Plum Hill or the Peach Orchard. He moved his two divisions off LRT and out to that position. He did so without orders and in so doing left a huge gap in the Union line. Luckily, Meade had the men and the time to plug that gap as Longstreet launched his attack. And in doing so, Meade also strengthened his position on Little Round Top. Two divisions of Confederate troops launched almost simultaneous attacks Sickles’ position and Little Round Top. The Union Signal unit provided a running report of the battle. As units weakened and buckled, they were quickly reinforced.

When Longstreet’s Corps arrived at the Emmittsburg Road that was to be their line of departure, they found themselves impeded by Sickles’ advance position. This disrupted Longstreet’s plan of attack. But attack they did. Wave after wave of rebels assaulted those hills but with little overall success. Late in the day, a Maine unit under LTC Chamberlain found themselves depleted (many wounded) and almost out of ammunition. He was the southernmost unit on the line and he knew that if he failed to hold that the entire line was in jeopardy. He uttered the infamous infantry order: “Fix bayonets”. He then led a charge down from Little Round Top but in a way that his men moved west as they went down the slope. It was described as a “swinging door” attack. It broke the back of Hood’s now demoralized attackers. For this action Chamberlain was awarded the Medal of Honor. Longstreet’s long day was over. Heavy fighting and numerous casualties occurred in places named the Peach Orchard, Devil’s Den and the Wheat Field, but overall the Union line held.

In the north, Ewell’s men fared no better. They were attacking up steep and heavily wooded slopes against an enemy that had had a day and a half to develop their defenses. A solid wall of rock or timber or earth awaited them at the top. Few got there. Along the bottom of the Culp’s Hill ran a stream that the local farmer had dammed to provide water for his cattle. This pond was too deep to cross so Ewell’s men were channeled east where they merged with other units causing confusion among the officers directing the attack. A solid wall of lead rained down as the Rebels tried to cross the shallow but wide stream = they had no cover. Many died and few reached the wooded slope; many fewer scaled it. Ewell had indeed been held in place until Longstreet was ready, so his attack was soon thwarted by nightfall as well as heavy losses.

Throughout the course of the day, Lee – knowing that he himself could do little to influence the day’s outcome seemed to be out of the picture. He is thought to have been suffering an angina attack that was sapping his strength and maybe even clouding his thinking. He had been awake until the wee hours of the morning and it is thought (though not recorded) that he slept most of the day.

His plan for Day 3 would be thwarted by Frustration and Fuses!

A game of Hide & Seek = a long and unnecessary Rebel loss!

Whatever it is, war is not child’s play. Yet, I present for your consideration that the morning of Day 2 at Gettysburg was something of a game of Hide & Seek played out by thousands of soldiers on both sides many of whom would be dead by nightfall!

As July 1, 1863 turned over into July 2nd, the name of the game was movement and consolidation at Gettysburg. From the west and the south, elements of both armies continued to arrive throughout the night. On the Rebel side, except for MG Johnson’s division which moved to oppose Culp’s Hill far to the east, other arriving Rebel units simply bedded down for the night, most behind Seminary Ridge. Only a small portion of Lee’s army had even seen (in this battle) a Yankee soldier much less fired their weapons.

On the hills immediately south of the city, most Union soldiers were toiling through the night to improve defensive bulwarks expecting an early morning attack that never came. One major exception was the 10,000-man Union Third Corps under LTG Sickles. They had arrived in the wee hours of the morning after an all-day march, Sickles had them bed down on the inner slope of Little Round Top. They made no effort to prepare a defense.

For his part, Meade had very little precise information about Lee’s forces. Ewell’s Corps of three divisions was to his north and east. Heth’s division of Hill’s Corps had borne the brunt of the fighting on Day 1 and was off to the northwest recuperating. Meade knew nothing of the exact whereabouts of the remainder of Lee’s men most of them commanded by the wily veteran LTG Longstreet. Seminary Ridge was playing its role in masking the arrival, disposition and movement of much of Lee’s army.

But Meade was confident in his plan, the plan proposed by BG Buford and most ably executed by LTG Hancock through the evening and night. Also in the wee hours of Day 2, Hancock had briefed Meade and handed off command of the defensive line. A major surprise of the morning for Meade was to find that Sickles was executing a reconnaissance in force of the area in front of the designated defensive line along the hilltop. The major disappointment is that he was doing nothing to improve his position on Little Round Top.

From Lee’s perspective, it was quite clear as to what Meade’s plan was. As startled as he might have been when he first glimpsed the Cemetery and its adjacent hills when he had climbed into the cupola of the Seminary late in the afternoon of Day 1, he immediately appreciated what Buford had seen as the strong defensive position that they afforded Meade. Somehow, Lee had to displace Meade’s men before they had full superiority in both terrain and numbers. It was also quite obvious that Meade was building his line from north to south. That would leave his southern (left) flank the least prepared and most vulnerable. In order to best prepare for such an attack, Lee needed to know where that flank ended. Early in the morning, he had dispatched one of his engineers, a CPT Johnston, to scout that flank.

Meade obviously and necessarily had his entire logistic train and support force nested inside the protective hills. If his troops could penetrate there, he could all but destroy the Army of the Potomac. Over breakfast, Lee gave Longstreet his marching orders (quite literally). He was to move his two divisions south behind the cover of the Seminary’s long ridge and after swinging around the end align his troops along the roadway, form up and attack in force up the Emmittsburg Road, in fact, be probing for any Union troops that were forming the left flank, with the aim of defeating them and striking into Meade’s rear area just over the rise. Lee seemingly never stopped to ask why Meade would leave such a huge hole in his defensive line. He only knew what he thought he knew: that Little Round Top was essentially undefended.

If Johnston was the SEEKER, then Sickles was the HIDER. Johnston was seeking the left flank but in reality it didn’t really exist. There were perhaps 10,000 men on Little Round Top but completely out of sight of any observer from the west — or the south (Big Round Top) for that matter. They were doing nothing to construct any defensive ramparts on that hilltop. Johnston had come and gone long before Sickles made his fateful decision to shift forward and occupy the Peach Orchard and the valuable terrain behind it.

Lee’s entire Army of Northern Virginia was at the north end of the battle field. He had no units occupying the long ridge south of the Seminary. Whatever scouts or skirmishers watching the Union lines where not reporting back to Lee’s HQ. He relied solely on the one-time observations of a single – if trusted – aide. There was no one in place to inform Lee that 10,000 men were on the move and setting up a skirmish line exactly where he intended his soldiers to be in a few hours. This has to be recorded as one of the biggest blunders in military history. Within 24 hours, Lee will have aligned perhaps as many as 150 cannons on that same ridge but through most of Day 2 he had NO ONE occupying it and spying on the Yankees! Seemingly a brigade of MG Anderson’s division (of Hill’s Corps) was moving onto the east facing slope of Seminary Ridge, but he also was not in contact with Lee.

Sickles had won the game of Hide & Seek and eluded detection of his massive presence. Lee would attempt to hide his advancing attack force, more or less successfully, but to no real gain.

Not long after Longstreet began his 2-mile trek, he was made aware that there was a Signal unit on Little Round Top. Had he proceeded as planned, his force would have been visible to them long before they had arrived at their point of departure for their attack. That unit could easily have relayed his position and ruined the element of surprise that he was relying on. He was forced to backtrack and move closer to the slope of Seminary Ridge to mask his advance. Having had to wait for the final units to round out his meager two divisions, he was already late in stepping off to the battle front. This forced maneuver only delayed his attack further.

While Longstreet’s long column was snaking around in the west, Sickles moved his entire corps without being observed by a single Rebel soldier. For the second time in the day, he had successfully (if unintentionally) hidden his troops from the enemy. Now they waited, hidden among the peach trees, lurking in the dense Rose Woods, sweating in the head-high stalks of wheat. A ‘lucky’ few were crouched in the cool shade of the boulders that comprised Devil’s Den. Soon many of them would be dead, wounded or captured!

Much like MG Heth’s approach through the forest on the morning of Day 1, MG McLaws’ division was anything but stealthy in their march south. They were attempting to stay out of sight of the signal unit but they were too far west to be heard. McLaws swung his division around the southern end of the ridge intending to march in formation, pivot and align to attack northward as soon as MG Hood’s division was in place to their rear.

There is an old military adage that a battle plan lasts only until first contact with the enemy. Nothing could have been truer on that hot July afternoon. As soon as McLaws’ lead elements rounded the turn, they were staring into the barrels of Sickles’ artillery that occupied the shoulder of his formation where it turned northward between the orchard and the woods. We know that Longstreet had sent his artillery battalion ahead of the infantry column and that they had set up just south of where McLaws rounded the end of the ridge. It is uncertain if they had been detected by the Sickles’ men. It hardly matters whether or not Sickles was aware of their presence, they were sitting in the exact position that Lee was expecting McLaws and Hood to align for their attack.

In simple terms, chaos ensued. Under fire from at least 20 cannons and a large part of MG Humphreys’ division, they were hugging the dirt in sheer survival mode. It wasn’t until the rest of McLaws division moved into place a bit to the south that these lead elements were able to return fire.

Earlier, Longstreet had argued against Lee’s attack plan, offering at least two alternatives which he thought had a better chance of success. He was still in a pique and was trailing behind Hood’s division far on the west side of Seminary Ridge. With no appreciation of the dire position McLaws had stumbled into, he was sending messages urging McLaws to initiate the planned attack in accordance with Lee’s orders. Nothing of the kind was going to happen!

In a quick reassessment of the situation, Hood slipped past McLaws’ rear and moved his division in line with McLaws all facing to the east. He was then aligned against Birney’s division lurking in the Wheat Field and Rose Woods. While McLaws was largely pinned down by the constant fire raining in on him, Hood’s men charged into Birney’s. Some of the heaviest fighting of the campaign took place in this compact killing zone. The same terrain changed hand multiple times over the course of the afternoon. Words like Meat Grinder, Hamburger Hill, Slaughter House, and Valley of Death have, over the years, found their way into military jargon. Longstreet’s attack could encompass them all. Brutal, close quarters, hand-to-hand fighting was the order of the day.

Meanwhile, Meade’s command staff was working hard to back-fill the gap left by Sickles’ brash movement. LTG Sykes Fifth Corps was slowing but effectively moving up to occupy Little Round Top. While much of the attention and credit for the Union success there has been placed on the 300 men of Joshua Chamberlain’s 20th Maine Regiment, his brigade commander COL Vincent and indeed the rest of Sykes’ Corps deserve a higher place in history for their timely and effective appearance at the south end of Little Round Top. They plugged the gap between Devil’s Den and Little Round Top, preventing any of Hood’s division from slipping through, cresting the ridge and penetrating the Union rear area. They also effectively covered Sickles withdraw at nightfall.

Once again, Lee had missed an opportunity to damage the Union Army further. Had he had any sizable unit on the crest or south slopes of Seminary Ridge, had he placed any artillery there, he could have further decimated Sickles’ Corps as they withdrew, battered but undefeated!

Anderson’s division of Hill’s Corps at the Union line to the north of Longstreet’s main attack line threw themselves against the Union line on Cemetery Hill. But just as their comrades to the south, they had little success and withdrew at dusk.

No one in the Confederate command staff seemed to fully recognize — much less exploit — the gap that Sickles had left between his right (northern) flank and Hancock’s left (southern) flank on Cemetery Ridge. It might very well have come at great cost, but seemingly Anderson could have – in a movement not unlike the following day’s attack by Pickett – pushed at least a brigade through that gap at great threat to the integrity of the Union line. Such an attack would have undoubtedly relieved some of the pressure being brought to bear on Longstreet’s men to the south. [I have termed this area The Saddle and discuss it more fully in Section 30h.]

Precisely what Lee was doing throughout the afternoon of 2 July is not faithfully recorded. It is highly likely that he was napping in his HQ near the Seminary, confident that his plan of attack was going to succeed. He had been awake well into the early morning hours after his visit to Ewell’s HQ on the far eastern side of town. He was one of the oldest men on the field and was thought to be somewhat ‘under the weather’ at that point in time as well.

If it ever needed re-enforcement that a Commander’s best intentions and battle plans can blow up in his face for the lack of a simple move of a chess piece, Day 2 at Gettysburg is a perfect example. The failure of the Confederate Army to detect Sickles’ advance, the failure to exploit the two gaps in the Union line that that move had created, the failed attacks on Chamberlain’s position in the woods of Little Round Top are perfect examples of the need for vigilance and reassessment of one’s plans once the battle begins to unfold.

Although not as simple as Hide & Seek, war is a game played largely without rules!